Chicago has a rich and storied history with labor unions that dates back to the late 1800s. Key events such as the Haymarket Riot, the Pullman Strike, the “Little Steel” strikes, and the formation of the Chicago Federation of Labor illustrate the city’s dense labor history.

In the late 1880s, Chicago was the epicenter of the industrial world. Many immigrants flooded the city, drawn by the opportunities from the meatpacking industry and its prime location in the middle of the country. As more workers entered local Chicago industries, more demands for better working conditions, shorter work days, and higher wages began to surface.

Numerous significant events and figures have shaped the history of Chicago’s unions, playing a crucial role in the development of modern labor organizations.

The Haymarket Riot

On May 1, 1886, a nationwide strike for an 8-hour workday began. On May 4, a meeting was held in the Chicago Haymarket to protest police brutality against union men who were injured and killed while picketing at McCormick Harvesting Machine Company.

During the Haymarket protest, police ordered a peaceful dispersion of protestors, a bomb was thrown towards the officers by an unknown person. The police responded by firing into the crowd. This became known as the “Haymarket Riot,” though it is more aptly called the “Haymarket Tragedy.” The ensuing anti-labor hysteria effectively killed the 8-Hour Day Movement.

The Pullman Strike

In 1893, the American Railway Union (ARU) was formed in Chicago, and membership was open to all white railroad employees, including coal miners, longshoremen, and car-builders, all of whom were employed by a railroad. Under the leadership of Eugene V. Debs, the union had some early victories, and membership swelled.

Pullman workers were fed up with the company and reduced wages and had attempted to negotiate. However, they were getting nowhere, and the workers launched a strike against advice from the ARU. The Pullman Company refused concessions and tried to wait them out. The ARU finally took a stand and boycotted all ARU workers’ handling of Pullman cars. Workers in the Pullman factories began a strike on May 11, 1894, crippling rail traffic nationwide as Pullman cars were in wide use.

It wasn’t until the strike affected U.S. mail that the government got involved. Even though the government was uncomfortable with labor actions in general, they issued an injunction against the boycott, citing the Sherman Anti-Trust Law of 1890 – ironic since that act was enacted to combat big business monopolies.

Ignoring Illinois Governor Altgeld, thousands of U.S. Marshals and Army troops were deployed, completely overshadowing the real plight of the Pullman Company workers. The clashes resulted in dozens of deaths and numerous injuries. The injunction also led to the imprisonment of many key leaders, which weakened the American Railway Union (ARU) and the strike effort.

Refusal by Debs and the ARU to obey the injunction led to indictments, and President Cleveland appointed a commission to investigate the matter.

While the public had been against the strike, George Pullman was heavily criticized for his policies that led to the strike.

The Pullman Strike had a significant impact across the nation. It showcased the strength of organized labor and compelled the government to take corporate paternalism into account. The injunction reinforced the federal government’s authority to maintain the free flow of interstate commerce and effectively rendered strikes illegal.

The Republic Steel Massacre

The “Little Steel Stike” of 1937 resulted in the loss of ten lives. Several small steelmakers, including Republic Steel, refused to sign a union contract at the directive of U.S. Steel (Big Steel). The result was a strike called by the Steel Workers Organizing Committee (SWOC) of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). In a show of support and solidarity, hundreds of SWOC sympathizers gathered at Sam’s Place on Memorial Day. When the crowd began to march toward the Republic Steel Mill, they were stopped by a formation of Chicago police, who fired into the crowd and pursued those fleeing. In the melee, ten demonstrators were killed.

The Chicago Federation of Labor (CFL)

The Chicago Federation of Labor (CFL) began as the General Trades Assembly and received its charter from the American Federation of Labor (AFL) on November 9, 1896. The CFL was established during a tumultuous period in labor history, following the Haymarket Riot, Pullman Strike, and the Republic Steel Massacre, igniting a wave of labor activism. Labor leaders recognized that their collective voices carried more weight. The first president of the CFL was bricklayer Thomas Preece, and within its first decade, the organization had nine different presidents:

- John Fitzpatrick – an Irish immigrant and President of Horsehoers Local 4, Fitzpatrick was a committed unionist who fought against corruption and cronyism and plagued other unions. His contributions include the weekly news publications and the creation of a Labor Party to bring labor issues into the political conversation. He was also vocal about racial, social, and economic justice. With his dear friend, “Mother Jones,” they led the steel strike of 1919. Fitzpatrick led the CFL for four decades, weathering the two World Wars, the Great Depression, and multiple strikes, including the Little Steel Strike and Memorial Day Massacre of 1937.

- William A. Lee – President of Baker Drivers Union Local 734 and VP of the CFL, was elected president after John Fitzpatrick’s death. He served for nearly 40 years. During his time, Lee presided over the merger between the CFL and the Cook County Industrial Union Council, South Chicago Trades and Labor Assembly, and Calumet Joint Labor Counseil in 1962. Lee’s work with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. inspired his lifelong mission to fight for equality. Upon Dr. King’s death, Lee said, “Labor will join all others of goodwill to take up the burden and the challenge he has left us…to eliminate all poverty, blight and discrimination.”

- Robert Healey – under his leadership, the CFL partnered with Cesar Chavez to support California’s farmworkers in 1990. In 1993, the CFL also supported the Illinois Labor Network Against Apartheid, hosting Nelson Mandela at Plubmers’ Hall.

- Don Turner – during his presidency, the CFL launched the Workers’ Assistance Committee (now the CFL Workforce and Community Initiative), which helped union members who lost their jobs due to layoffs or closings.

- Dennis Gannon – he continued the CFL’s critical role in civic and political affairs. In 2007, the CFL helped boost President Obama’s campaign, all while ratifying a 10-year contract in the run-up to Chicago’s bid for the Olympics.

- Jorge Ramirez – under his leadership, the CFL fought against a rising tide of anti-unionism, and he led the charge against pension cuts. His work earned him a role on the AFL-CIO Executive Council.

- Robert G. Reiter, Jr. – the current CFL president, continues to fight, winning new rights for Chicago workers and helping those navigate a once-in-a-generation pandemic.

Today, the CFL continues to support and be involved in significant events, initiatives, campaigns, and projects in Chicago and the greater Cook County. The CFL currently has over 500,000 members and over 300 affiliated unions throughout Chicagoland.

#UnionStrong

Vogelzang Law is proud to partner with unions across Chicago and the State of Illinois. We are honored to count numerous unions representing boilermakers, bricklayers, steelworkers, insulators, pipefitters, laborers, sprinkler fitters, carpenters, and many more as valued partners, colleagues, and friends.

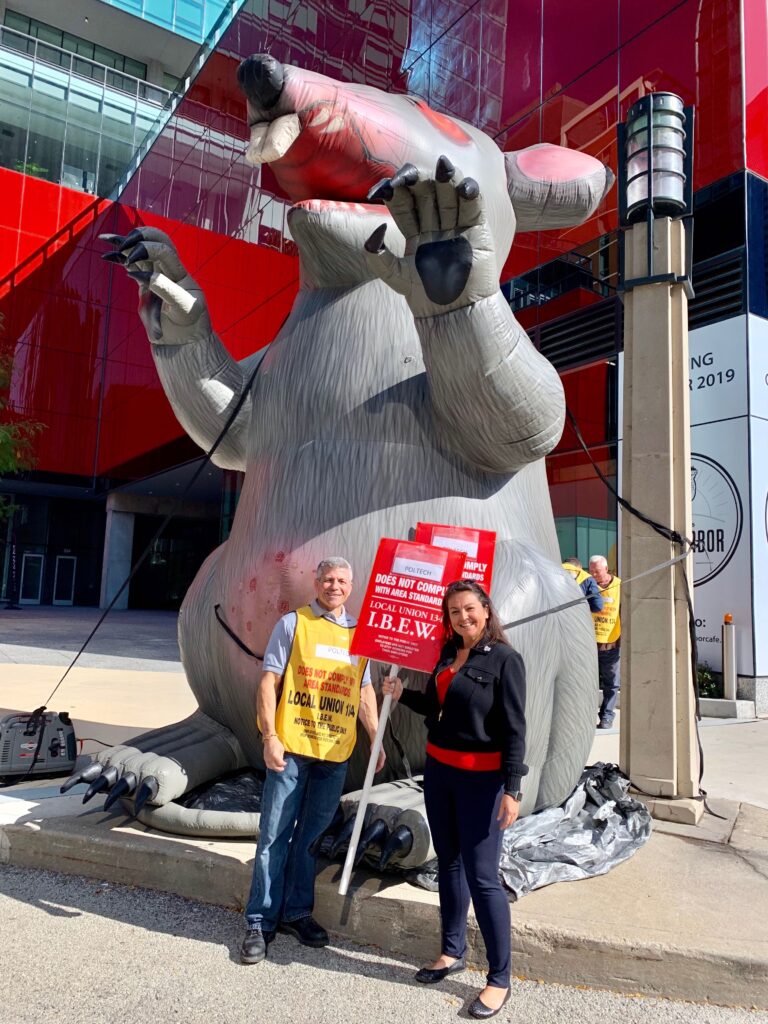

At Vogelzang Law, we always stand by our unions. We show our support during union strikes by bringing donuts and coffee to anyone we see protesting in front of the scabby rat. We want all unions to know they have our support event during a protest.