As an attorney representing people with cancer due to asbestos exposure (primarily mesothelioma), I have seen families face stage IV cancer in an up-close and personal manner, watching them in the initial stages of diagnosis, through the treatment, and after the loss.

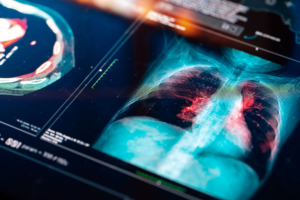

Mesothelioma usually isn’t detected until it’s in late stage, with initial symptoms like shortness of breath and a pain in the side. When the patient goes in for a CT scan, the tumor looks like an orange peel slowly wrapping around the lung and inhabiting the mesothelium, which is the sausage casing that envelopes all of our lungs.

For most of my career, I have resided in the United States and worked exclusively with individuals that were exposed to asbestos here. Recently, I had an opportunity to help veterans of the Greek and Italian navy who are currently being treated for mesothelioma from asbestos exposure while working on ships. Both Greece and Italy purchased countless United States Navy ships, renamed them and gave them a second life in their own navy. It was an excellent way for the United States to upgrade their fleet and sell warships to their allies. It also gave Greece and Italy the ability to grow their fleet faster and have similar technology to the United States. Unfortunately, the asbestos insulation and replacement asbestos insulation was included in the sale.

These transactions occurred throughout the 1970s and 1980s when all parties involved should have known about the hazards of asbestos. Just like sailors from the United States, Greek and Italian sailors cut through old, existing asbestos insulation to get at the internal valves and pumps for repair, scraping off worn-out asbestos gaskets and putting asbestos mud on the old boilers and generators. Not only was the existing insulation left on the pipes, pumps and valves, but replacement parts containing asbestos were also still in the storeroom, thus creating little incentive to purchase new, non-asbestos-containing insulation and replacement parts. Much of the asbestos-containing material (ACM) was originally manufactured in the United States using asbestos fiber mined in Africa and imported by the container in 100-pound gunny sacks. U.S. manufacturers mixed the raw asbestos fibers with a few other ingredients and sold millions of tons of ACM that was later installed on the warships, sometimes by the sailors themselves.

Similar to the men before them, the Greeks and Italians weren’t given any warnings about the danger of asbestos fibers. They smoked cigarettes while asbestos dust settled in the air, a practice that can increase your risk of lung cancer by up to 90 times of that of a normal population. They didn’t wear masks. They didn’t limit their time around dusty areas, and the rooms in the ship provided little, if any, ventilation.

In 2019, I flew to Bari, Italy to meet with seven men who all worked on old U.S. warships and were all living with mesothelioma. To put this in perspective, mesothelioma is an extremely rare cancer for the general population. In the United States, a country of 300 million, there are only 3,500 cases per year or .001 percent of the population. However, the statistics are much worse for the population of people that worked with and around asbestos for hundreds of hours aboard a ship. At this point, mesothelioma is still a terminal disease and most people have a life expectancy of around 12 months from the date of diagnosis.

The men in Bari were all in good spirits and happy to meet an American lawyer. It appeared they hadn’t been together in a long time and they enjoyed talking about their work aboard ships in the Navy. I discussed their asbestos exposure with each of them and the potential routes to compensation. Some of them had worked in U.S. ports while being exposed to asbestos, while others also worked aboard U.S. ships while the ship was flying the U.S. flag. All of them had worked on ships that contained ACM manufactured and sold in the United States. Many of those manufacturing companies are bankrupt today, but they have established trusts as part of the bankruptcy to compensate some of these Italian and Greek sailors. Unfortunately, the payouts are little consolation for these men and their families knowing what they are losing. Despite this heavy backdrop, the men mostly smiled, some of them eager to show off their English skills, and recounted their past lives.

We then traveled across the ankle of Italy to the gorgeous town of Naples, stopping for delicious pastries, espresso and pizza along the way. When we arrived at a law office, there was a very similar group of men all suffering from mesothelioma.

Early in 2020, just before the pandemic lockdowns, I also traveled to Athens and Peraeus, an international port town in Greece. There, I met with a very gentle man who had been a proud sailor in the Hellenic Navy. He beamed with every story and every answer to my many questions about all of the U.S. ships that he had served on.

The Greek gentleman ended up working in California for some time, so he had a strong case that we could bring to a California court. I spent three weeks in Greece working with him and several of his colleagues. It was a tremendous experience and my last chance to travel abroad.

It was also tough to see such a similar group of hard-working veterans dealing with the same terrible cancer from a mineral spread around the world from various, almost inevitable, machinations. Eventually, this cancer will be mostly gone from the U.S. and Europe. Unfortunately, asbestos is still frequently used in India, China, Russia and the continent of Africa with little heed for safety. The only thing more frustrating than cancer is watching people get a preventable cancer that cuts their life short. Asbestos is an international phenomenon, just like the cancer it causes. Hopefully the work being done in medicine will help extend the lives of the victims and the progress in occupational medicine will help educate corporations and countries across the world to prevent the next occupational tragedy.