By MICHAEL G. MATEJKA

Willard Tipsord was a father, foster parent, husband, grandfather, and for over 30 years, a member of Carpenters Local 63 in McLean County, Illinois. As a young newlywed, he went to work at Bloomington’s United Asbestos & Rubber Company (UNARCO) plant to provide for his family. On May 1, 1989, at age 57, he died of mesothelioma, an asbestos-related cancer.

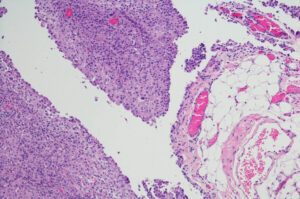

Tipsword was diagnosed in his late 40s, and despite trying every available treatment, it was a death sentence. Asbestos fibers lodge themselves into the lungs, causing cancer and reducing oxygen flow to the bloodstream, slowly suffocating victims.

Tipsord’s daughter Cheryl remembers her father as a “picture of health. He was tall, lean and muscular. He never drank. He worked all day and then through the evening, building cabinets and homes.”

It was hard to see that strong, healthy young man dying day-by-day,” Cheryl recalls. “His life was cut short because he was knowingly exposed to a hazard. He did not have the human right to work in a safe environment.”

His granddaughter, Dr. Ericka Wills, was six when he died. Today she is a labor educator and activist, her inspiration a strong union man whose life was stolen from him. “Today as a union activist and Labor Studies professor,” she said, “I help workers and students gain a sense of empowerment by knowing that they have the right to create and engage in a democratic workplace. In doing so, I am honoring the men and women, like my grandpa, who gave their lives in the fight for safe workplaces, fair wages, and dignity at work.”

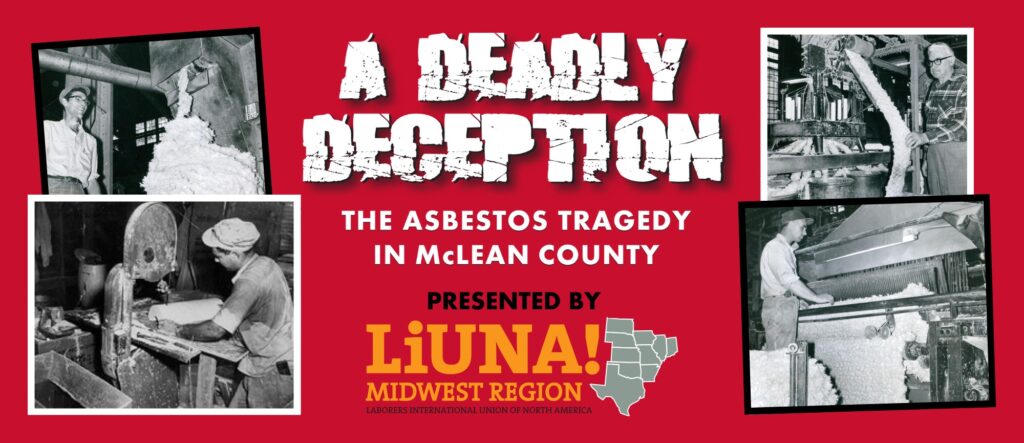

Willard Tipsord is one of 133 verified, and countless unverified, asbestos-related deaths in McLean County. The McLean County Museum of History’s newest temporary exhibit, A Deadly Deception: The Asbestos Tragedy in McLean County explores the history of the Union Asbestos and Rubber Company (UNARCO) manufacturing plant on Bloomington’s westside, which operated from 1951-1972. It uncovers the workers’ experience, their fight for better working conditions, and the onslaught of litigation that followed.

However, this exhibit also tells a story larger than just McLean County. It is a universal story of people being sacrificed, forced to endure toxic conditions and environmental hazards all in the pursuit of profit. The Museum believes this exhibit illustrates a national tragedy on a local scale, all the while educating the public about the dangers of asbestos and honoring the people who lost their lives.

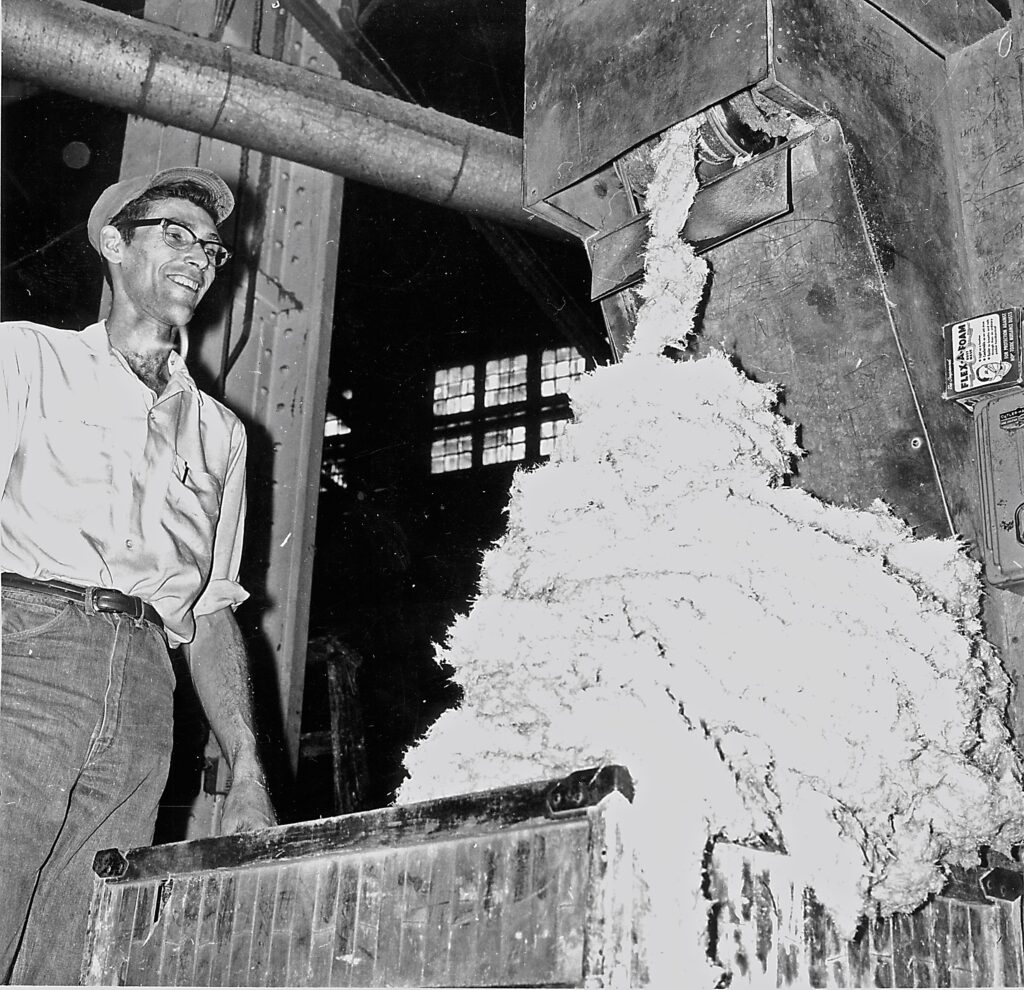

Photo caption: Bill Mau, who would die of asbestos-related disease, empties asbestos into a weaving machine at the UNARCO plant in Bloomington. (McLean County Museum of History photo).

Asbestos is a naturally occurring substance composed of fibrous silicate minerals resistant to heat and corrosion. Humans have used asbestos for thousands of years, but late nineteenth century advertising billed it to be a miracle product, skyrocketing its popularity during a time when fires were one of the greatest threats to homes and businesses. Flame retardant and an excellent insulator, it could be woven or felted into fabric or combined with other materials for hundreds of purposes.

At UNARCO burlap bags full of asbestos from South African mines would arrive; the bags would be openly dumped and then woven into asbestos fabric for insulation. Each process increased the airborne asbestos dust. UNARCO employee William Johnson remembered: “I worked on the day shift, and there was a beam of light that would come through the window. (The asbestos) looked like millions of diamonds in the air.” Otto Kessinger said that: “At the end of the plant where I worked, you could look up . . . it looked like it was snowing with asbestos fiber.”

Dust masks were sometimes provided, but workers’ masks were inadequate. Management and technicians were given higher-end, more expensive masks. Workers were given inexpensive masks, like the disposable COVID masks of more recent memory. Even those masks were not always available. Cheryl recounts that her father and his co-workers would use kerchiefs to cover their face. Management demanded they remove them.

Workers were frustrated by the provided masks. Charles Hammond also died from asbestos exposure at UNARCO. His wife Charlotte recalls: “They furnished masks, but they were the wrong kind. They’d get clogged up and you couldn’t shake it out. Or they would go for months without masks. Then they would get some and they’d be the wrong kind again. When you’re young you believe the company. You need a job.” Workers headed homeward with asbestos fibers clinging to their clothing that exposed their families. In some cases, family members also succumbed to the disease.

Although the workers were reassured the workplace was safe, UNARCO continually monitored the workers’ health through regular x-rays. Workers who showed possible deadly exposure were “eased out.” Company management would visit the worker and family at home, admitting the disease. A settlement offer was extended, provided the worker agreed not to sue.

UNARCO established their own insurance company, Associated Safety & Claims Services Inc. Plant official W.H. Haines admitted in later testimony that this was a “dummy fund” so that employees would not learn the company was self-insured.

In 1970 Owens-Corning bought the UNARCO facility. They sent their own industrial hygienist to evaluate the plant. The resulting report said that: “The atmospheric conditions in the work environment of this plant are unbelievably bad. … No consideration was given to protecting the health of the workforce. … The outdated equipment and methods of handling prevent proper control under present conditions.” Owens-Corning ceased local asbestos production in 1972 and manufactured industrial sinks at the plant.

UNARCO was not an outlier — multiple corporations manufactured and used the material.

By the late 1960s asbestos’ deadly nature was slowly exposed. Multiple lawsuits were filed by disabled workers, eventually sinking the industry. In July 1982 UNARCO’s successor company filed for bankruptcy, quickly followed in September by industry leader Johns-Manville. A trust fund for victims was established from these multiple bankruptcies.

From 1989 until 2010, this trust processed 306,939 claims, settling 188,406 for a total of $262,248,992. Owens Corning declared bankruptcy in 2000. Bloomington attorney James Walker filed multiple cases for workers. The discovery process revealed how UNARCO withheld evidence of asbestos’ dangers from its workers.

Asbestos not only costs workers their lives, but it also costs businesses and local governments to remediate the asbestos and remove the danger.

The asbestos corporate cover-up is not unique. The tobacco industry is a known example, along with the recent lawsuits and deaths over the drug oxycontin. Now suits are being brought around “forever chemicals” used in cookware, clothing, and cosmetics. Legal actions are revealing that manufacturers knew the dangers decades ago. Consumer caution is important, but so is rigorous, government and agency testing to ensure public safety.

A Deadly Deception: Asbestos in McLean County opens at the McLean County Museum of History on September 7 and will be open through the summer of 2027. The exhibit sponsor is the Laborers International Union of North America, Midwest Region. To learn more, please visit mchistory.org. LIUNA 362 member Mike Matejka was the exhibit’s guest curator.