The history of asbestos dates back to prehistoric times, but it wasn’t until the Industrial Age that it gained notoriety. In the early 1920s, its harmful effects were recognized, but it was already used in countless ways. Past and current products made of asbestos include insulation (pipe, block, and cement); fireproofing acoustical products; textile and cloth products (asbestos gloves, blankets, etc.); joint compounds; gaskets, valves, asbestos-cement pipe and sheet material, ceiling tiles, wallboard, siding, roofing; and friction materials such as clutches and brakes.

Colloquially known as the “miracle mineral” due to its flexibility and heat-resistant properties, it is now a known carcinogen and the cause of many diseases, specifically mesothelioma, lung cancer, and asbestosis. It has been used in numerous industries, including the military, automotive, shipping, construction, manufacturing, power and chemical, and even NASA.

The mineral composition of asbestos includes silicon, oxygen, hydrogen, and other metal ions. The naked eye cannot see the microscopic needle-like fibers unless they are in large clusters. The three types of asbestos are chrysolite, amosite, and crocidolite.

The history of asbestos is full of innovation, but the cost of that innovation was human lives, often through subterfuge and negligence. As experts, doctors, and the public learned about the harmful effects of asbestos, measures were taken to mitigate the damage, but for many, it was far too late. Asbestos may have been useful historically but has undeniably caused extensive harm and devastation.

Asbestos in the Beginning: The Ancient World

Asbestos is found naturally in every corner of the globe and has a history that stretches back to the Stone Age.

- By 4000 B.C., asbestos was fashioned into wicks for lamps and candles.

- In 2500 B.C., workers in Finland were crafting clay pots containing asbestos to make them durable and fire-resistant.

- 456 B.C., the Greek historian Herodotus referenced using asbestos shrouds to wrap the dead before they were put into the funeral pyre so ashes would not be mixed.

- The Egyptians used asbestos to craft fine cloth for wrapping their deceased, ensuring their bodies remained safeguarded from decay and deterioration.

- The Romans wove asbestos fibers into cloth-like materials made into tablecloths and napkins.

Although asbestos had clear benefits, the Greeks and Romans recorded its detrimental effects on those who mined it. Strabo, a well-known Greek geographer, mentioned a “sickness of the lung” affecting enslaved individuals who worked with asbestos. Furthermore, a Roman historian, naturalist, and philosopher discussed the “disease of slaves” linked to asbestos exposure.

Asbestos from the Middle Ages to Modern Times

In 775, King Charlemagne of France commissioned a tablecloth woven from asbestos fibers, even then a material renowned for its heat-resistant properties. He wanted a table covering that would be safe during the many accidental fires occurring during the numerous feasts and celebrations. Much like his ancestors, King Charlemagne also wrapped the bodies of his deceased generals in asbestos shrouds, leading to cremation cloths, mats, and wicks for temple lamps made from chrysotile asbestos from Cyrpus and tremolite asbestos from northern Italy.

Fast forward three centuries and the First Crusade saw a coalition of French, German, and Italian knights fighting with a catapult (also known as a trebuchet) to fling asbestos bags full of flaming pitch and tar over city walls. By 1280, Marco Polo noted Mongolian clothing made from a “fabric which would not burn.” Polo also made the trek to a Chinese asbestos mine to disprove the myth that asbestos came from the hair of a wooly lizard.

Asbestos made numerous other appearances throughout the Middle Ages:

- From 1682 to 1725, during the reign of Russia’s Tsar, Peter the Great, chrysotile asbestos was mined.

- In 1725, a young Benjamin Franklin brought a purse constructed from fireproof asbestos materials to England (now in London’s Natural History Museum collection).

- In the early 1700s, Italians started making paper with asbestos, and by the 1800s, they included asbestos fibers in their banknotes.

- In the mid-1850s, the jackets and helmets worn by the Parisian Fire Brigade were made from asbestos.

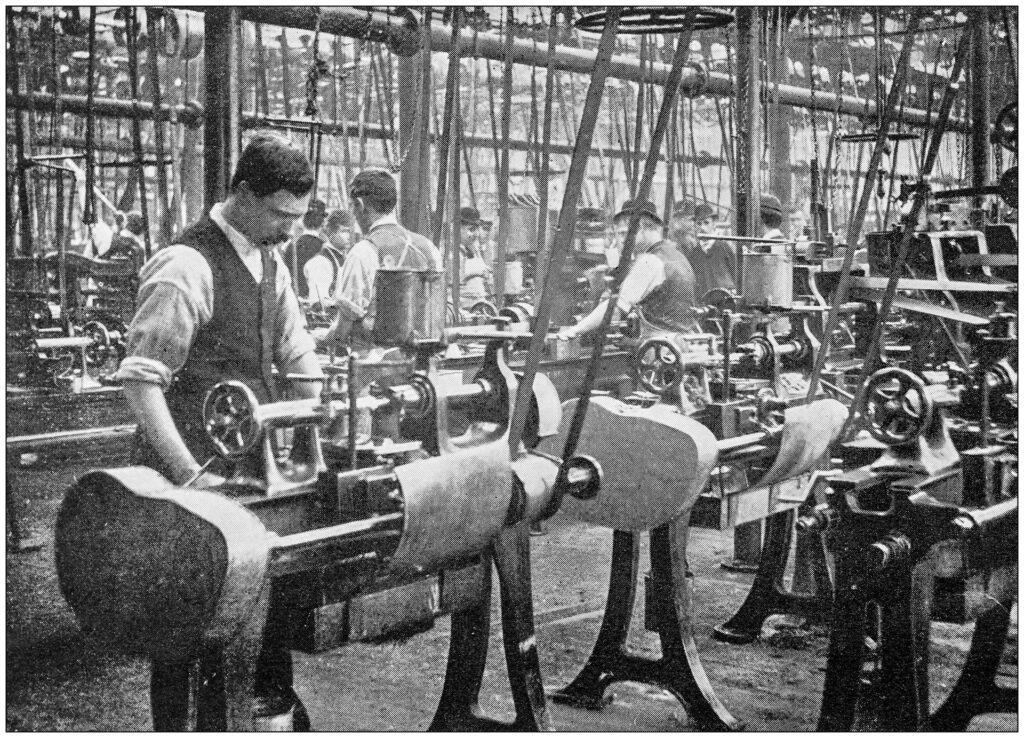

The 1800s marked the era of the Industrial Revolution, a period during which the production of asbestos thrived as a booming industry. Mining and manufacturing surged, and because of its diverse applications in practical and commercial settings, asbestos became increasingly widespread. The popularity of asbestos meant the health risks to those who mined, refined, and worked with it were at higher risk of harm.

Asbestos was unique for its exceptional resistance to chemicals, heat, water, and electricity. During the Industrial Revolution, this made it an unmatched insulator for turbines, boilers, steam engines, ovens, and generators. Furthermore, its flexibility made it an essential component for construction, serving as a binding and strengthening agent.

Asbestos Mining & Production

Asbestos mining originated in the early 19th century, with crocidolite (blue asbestos) first identified in Free State, Africa. In 1876, chrysotile (white asbestos) was found in Thetford Township in southeastern Quebec, leading Canadians to set up the first commercial asbestos mines.

In the early 1870s, major asbestos industries were established in Scotland, Germany, and England, while Italy had already been extracting tremolite asbestos for many years. Australia began mining at Jones Creek in New South Wales during the 1880s, and by the early 1900s, anthophyllite asbestos was being extracted in Finland. Amosite (brown asbestos) was identified in Transvaal, South Africa, and the production and promotion of chrysotile asbestos continued in Swaziland and Zimbabwe.

Asbestos mining and production relied on manual labor and wasn’t mechanized until the Industrial Revolution. As demand grew, steam-driven machinery replaced humans in mining and production.

By the early 1900s, asbestos production had grown to more than 30,000 annual tons worldwide. While men worked the mines, women and children contributed to the workforce, preparing, carding, and spinning the raw fibers.

From this boom came manufacturing companies. The H.W. Johns Manufacturing Company was established in 1858 by Henry Ward Johns. The company produced fireproof roofing materials composed of burlap, asbestos, tar, and other components. They sourced anthophyllite asbestos from a quarry located on Staten Island. Before his death, which was believed to be due to asbestosis, Johns broadened the applications of asbestos. In 1901, H.W. Johns Manufacturing merged with the Manville Covering Company, creating Johns Manville, which became the leading manufacturer of asbestos products in the United States.

In 1896, the British company Ferodo made the first asbestos brake linings for new horseless carriages. In Germany, three years later, the first patent was issued for the manufacture of asbestos cement sheets. Klinger, an Austrian company, produced high-pressure asbestos gaskets in 1900, while Italy developed the first asbestos pipes in 1913.

During the 1960s and 1970s, asbestos mining saw a significant increase in the United States, leading to the establishment of numerous operations on the East Coast and in California. The King City Asbestos Company (KCAC) mine in west-central California was the last operational asbestos mine in the U.S., shutting down in 2002.

The Unstoppable Asbestos Industry

The asbestos industry thrived even in the face of ongoing health warnings. By 1910, global production had surpassed 109,000 metric tons, marking a threefold increase in just 10 years.

The U.S. was the world’s largest consumer of asbestos products due to its rapidly growing population and demand for cost-effective, mass-produced construction material, with Canada furnishing a steady supply. Although World War I caused a temporary slowdown in the industry’s expansion, World War II sparked renewed growth. By 1942, the U.S. accounted for about 60% of world asbestos production, with extra heavy use by the military.

The asbestos industry used its power and influence to conceal the dangers of asbestos from workers and the public, as proven by court documents. Workers were neither informed of the risks nor provided with adequate safety equipment.

Asbestos was a key component of many everyday products used by the construction and automotive industries. Products include:

- Cement

- Insulation (stove, furnace, pipe, electrical, thermal, etc.)

- Roofing and flooring compounds

- Siding

- Floor and Ceiling Tiles

- Automotive and airplane clutches

- Millboard and paper for electrical panels

- Gaskets (door gaskets for furnaces and stoves)

- Fillers and reinforcement for plasters

- Caulking compounds

- Paint

- Spray-on, fire-retardant coating

- Brake pads, linings, seals, and gaskets (cars, trucks, airplanes, etc.)

- Asphalt

Asbestos is also present in many consumer goods such as cosmetics, small appliances, and child’s make-up sets.

Asbestos consumption peaked in 1973 at 804,000 tons. By the late 1970s, the public had begun to understand the link between asbestos exposure and lung diseases, leading to the decline in its use.

Labor unions began to demand better working conditions, and individuals began to claim liability against companies knowingly exposing their workers to asbestos.

As one of the last countries to do so, the United States finally banned chrysotile asbestos in 2024. The new ban gives companies 12 years to phase asbestos out of the manufacturing process. Even though the last U.S. asbestos mine closed in 2002, workers are still paying the price.

The Harmful Effects of Asbestos

In 1897, an Austrian physician linked his patient’s respiratory issues to inhaling asbestos dust. A report from 1898 on asbestos manufacturing in England noted “widespread damage and injury of the lungs, due to the dusty surrounding of the asbestos mill.”

In 1906, Dr. Montague Murray documented the first death linked to asbestos at Charing Cross Hospital in London. The autopsy of the 33-year-old worker showed significant amounts of asbestos fibers in his lungs. Similar reports of fatalities due to “fibrosis” in asbestos facilities in Italy and France aligned with studies from the U.S. indicating that asbestos workers were experiencing unusually young mortality rates. By 1908, insurance companies in the U.S. and Canada started to raise premiums while reducing coverage and benefits.

In the U.S., Drs. Lynch and Smith were the first to link asbestos to lung cancer in the 1930s. They noted an excess number of workers with lung cancer from the local asbestos textile plant. By 1942, the then-director of occupational cancer studies at the National Cancer Institute declared that asbestos caused lung cancer.

Mesothelioma cases began to surface in the 1950s after cases were reported in Germany and the Netherlands. In the 1930s, researchers in South Africa related occurrences of mesothelioma with asbestos exposure, further noting that the cancer was also present in family members of works and communities where asbestos was mined.

Over the years, other cancers have been linked to asbestos exposure, including laryngeal cancer, ovarian cancer (often from talc use), various GI tract cancers (esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and colorectal cancers), and even kidney cancer.

Although asbestos is prohibited in numerous countries globally, its harmful impact is far from over. Because of its long latency period, mesothelioma, lung cancer, and asbestosis will persist in claiming lives and impacting communities around the world.

Vogelzang Law’s Commitment to a Cure

For over 20 years, Vogelzang Law has been committed to serving the cancer community. Beyond litigation, the firm works with charitable organizations nationwide to provide education, resources, and services for those affected by cancer. Learn more about how we can help you.